House of Lords Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities Tuesday 27 November 2018.

Gary Young presented to the House of Lords Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns providing evidence on the benefits of local leadership in placemaking and creative led regeneration, primarily using Folkestone in East Kent as a case study. He referenced to the positive effects of regeneration through projects in Hull and Liverpool as cities of culture and proposed this could be widened to a group of seaside towns.

Link Here to download final report of House of Lords Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns

Shortly after the committee Yvette Cooper published a similar idea promoting “town of culture.”

Link to Article by Yvette Cooper https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/dec/29/yvette-cooper-leads-call-for-town-of-culture-award-regeneration

Link to BBC Radio 4 on 31 December 2019 presented “Positive Thinking, The New Seaside” writer Farrah Jarral goes in search of a brighter future for neglected coastal communities, featuring ideas for scaling up with creative enterprises at New Brighton on the Mersey, Wirral. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000cq0c

Link to Impacts 18 longitudinal research programme dedicated to capturing the long-term effects of hosting the 2008 European Capital of Culture title on the city of Liverpool.://www.cultureliverpool.co.uk/news/impacts-18-a-cultural-legacy/ http://iccliverpool.ac.uk/impacts18/

Excerpts from Gary Young’s evidence in the transcript of the Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities Regenerating Seaside Towns Tuesday 27 November 2018.

“To investigate the challenges associated with creating developments on the seafront generally and in seaside towns in particular we need to look at the wider context. Many seaside towns developed during a time when the accommodation provided suited the time and a different type of use of the town for leisure. They are often in areas of natural beauty with the presence of the sea and coastline beaches, so development itself is constrained in a very significant part. Quite often, it has taken place one street back from the seafront with new developments, such as shopping. Therefore, you end up with almost a double front to the town. You have the historic front, and the aspect of what to do with it when it is exposed to weather has always been a challenge. Quite often, those have become slightly derelict and less intensively used, so that is the context in which investment in a sense is challenged. There are a few examples where people have acquired sufficient of that land to make a go at a composite scheme—for example, in Folkestone—but often the lack of ability to do things incrementally because of the scale of the challenge facing the seafront is larger than people perceive in an insular town”.

“We can continue to explore the example just referred to: Folkestone seafront. Folkestone benefited from the £11 billion spent on HS1. The point you are making is very valid. A seafront town has duality: it has a town to support and it has presence on the sea. It is challenging because that doubles your frontage. It is an opportunity, but it is a challenge. The train infrastructure for the majority of seafront towns has not really been pushed forward, because of the lower catchment. It is a fluke that a couple of towns such as Folkestone are on a through route and have benefited from that infrastructure. Phenomenal investment has kickstarted people’s confidence, similar to other Kent towns that have been part of Javelin, again on the back of huge national investment. Interestingly, other towns such as Blackpool or Scarborough existed because the people of Yorkshire wanted to travel to the west coast to holiday and people from the west coast wanted to go to the east coast, but the train services are pretty poor, compared with those from London to the south-east. That inability to get infrastructure spending to drive regeneration means you have the double whammy of a complex town with two fronts needing more infrastructure spend at a higher national level to generate it, which has happened in a couple of towns.

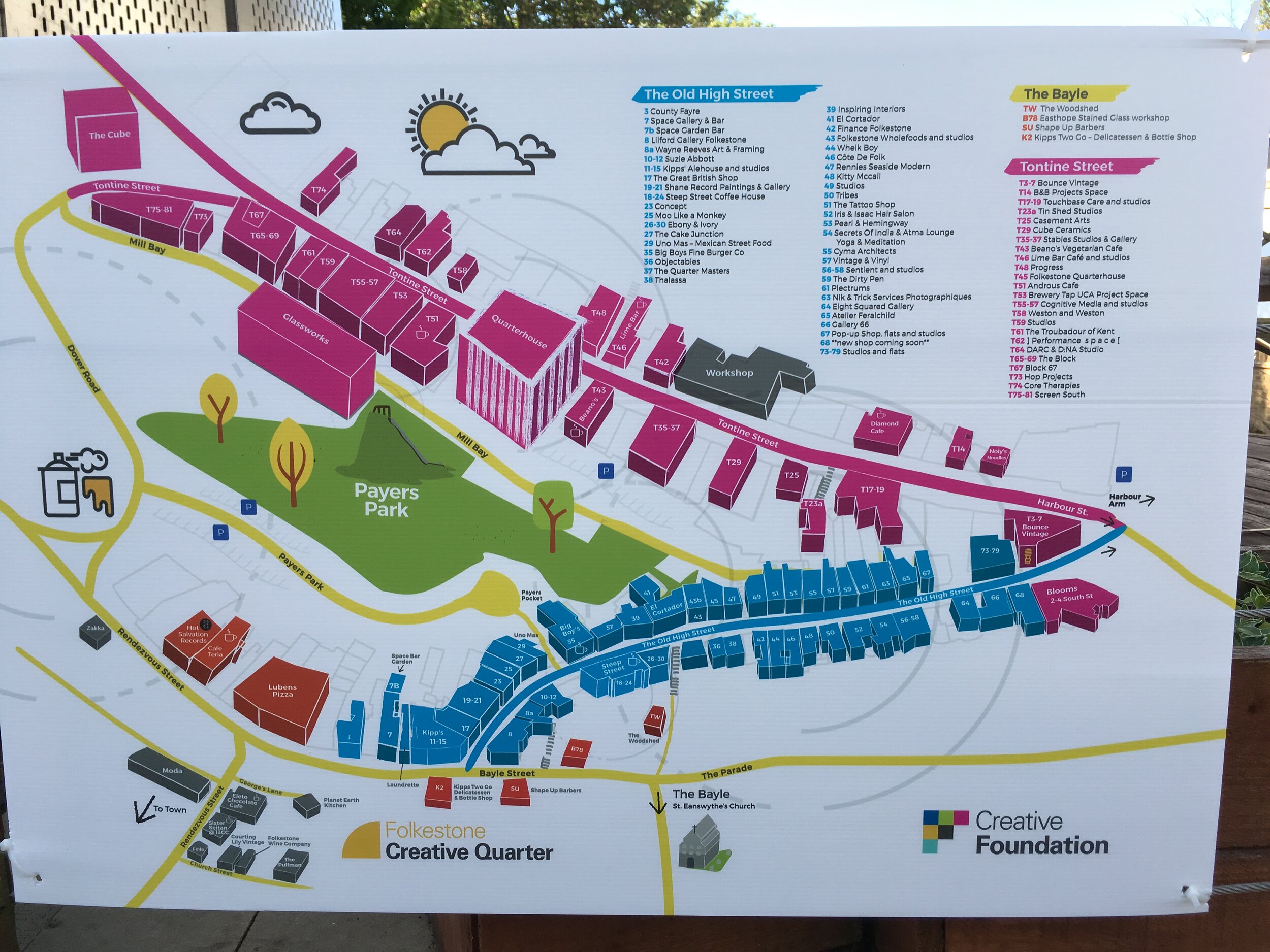

I have been doing research on a couple of projects in which Farrells has been involved over the decades I have worked with it. One of the big success stories has been The Deep in Hull—an aquarium that was funded by the National Lottery and finished in 2002. It is a successfully running charitable organisation that is very popular. It runs off its own revenue. There are occasions when you can find a gap in the national profile and major landmark visitor attractions can fit into a place well. The success is not just it as an entity; it is the fact that Hull achieved the status of City of Culture in 2017. There has been a great change of negativism to positivism in the past decade in Hull. That has been recorded by the University of Liverpool in a very interesting read called “Impact 18”. It studies the effect of the European City of Culture, which status Liverpool achieved in 2008, and how it has changed the percentage of negative news into positive news. It has influenced the way people think about their city, and globally the way the rest of the world thinks about a city. You cannot underestimate how important that is. While those two projects were based on big landmarks—the Tate moving to Liverpool and The Deep in Hull—it is now recognised that you can begin to achieve this in a way that Alex has described by doing small things and having a creative foundation formed around a project. That is again what has happened in Folkestone. The creative foundation was formed when the seafront development was created by the investor Roger De Haan, and it is a charity with a £2 million turnover that supports local businesses. It has purchased 80 properties; it has mediarelated creative activities, and it is looking for more space. For example, it has just become involved in the thing we have all seen on the news, Pages of the Sea, where local people created sand sculptures on 11 November. Folkestone was one of the initiators. This is the sort of thing that captures people’s imagination; it transforms, and the regeneration is part of the self-image.

Seafront towns with ports, fishing communities or tourism were often more outward looking than towns in rural areas, however the original identity has often been lost. There are ways to regain an identity with an accumulation of smaller creative projects which can shift mindset and generate more local sustainable investment. The approach taken by these initiatives recreates the sense of purpose and pride. Folkestone launched itself with single regeneration budget money, which the council decided to use to create land assembly. It created a partnership with a major wealthy landowner and the community which is now beginning to see the benefits. I spoke to the project manager during that period and he said that the key was leveraging other land. A series of amusement arcades—typically in a seaside town—needed to be brought in. The owners of the arcades were persuaded to sell to enable the work. He owns two bunches of amusement arcades and they persuaded him to concentrate on one. They then went on successfully to Dreamland Margate, so it was a win-win.

When we were involved in lottery projects before and after the millennium period there was scrutiny. For every project that got through, there were dozens that failed because they did 11 not meet the criteria, so of course there should be. That is when you are simply looking at capital from the lottery for a good cause. The issue is complicated when you have Heritage Lottery funding and there is a heritage aspect: you have to retain the presence of important and historic icons and monuments. For every one of those that turned into a profitable concern there are others that did not. I worked on Tobacco Dock in Wapping. It is not on the seafront but it is right on the river. You can argue that the Thames is the sea. That is still not used properly, but a fortune was spent on restoring it to good condition, but not good use. Therefore, scrutiny is vital. That was not lottery money but private money, but scrutiny is vital. For every project that has succeeded there are dozens that have been discarded. Piers are iconic; they are part of our culture. We tend to be drawn to iconic projects. The Deep, an aquarium, is an iconic project, and that succeeded, but quite often it is a mistake to look for iconic projects. You should start looking for smaller and broader-based investment in seaside towns, hence the reference to the Creative Foundation. When I was in Liverpool I was asked to join a project called Hidden Liverpool, which was funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. It was to identify a dozen derelict buildings in Liverpool, ranging from buildings near the pier to a reservoir in Sefton, and ask school students to get inside them and find out what their ideas were. It was organised in 2013 by a group called Placed. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/apr/18/beatles-old-buildings-hidden-liverpool-revives-special-places. This is part of the message that people start to understand their cultural environment and heritage better and learn about the business of restoration, so that for every one of those there is a business plan. Therefore, students are doing business plans. We do not do the plans; we design things for people, but students should be aware as they go through life that in developing culture there has to be the ability to find funding—crowdfunding or creative ways to bring funding from outside sources. http://www.hiddenliverpool.org.uk/news/63-future-city-exhibition-and-dragon-s-den-round-up

Understanding the economy of the work should be embedded in people from a young age. Of course, we understand as much as we possibly can; the final auditor is someone who has access to information that we do not necessarily have, but it is a question of understanding instinctively which projects will have life and succeed. I go back to Hull and the example of the aquarium. That project has been tried dozens of times across the country, and in London and elsewhere it has succeeded. That was probably a unique set of circumstances. I was pointing out the fact that you cannot necessarily from our point of view manufacture those perfect environments. You can understand it when you see it; you can understand how important it is, and obviously the longevity of a project, having seen some that have not had longevity, is vital.

I think that for place-making national policy has to encourage creativity, because that is one of the driving forces behind people’s pride in the place where they live. “Impacts 18”, the research project on Liverpool is really worth reading. It can be done in a very small way incrementally. Too often it is just seen as a big hit.