Presentation by Gary Young at London Planning and Development Forum, 3rd Dec 2019, titled Design Quality not Overcrowding.

Link here to download Gary Young’s presentation to London Planning and Development Forum 3rd Dec 2019.

Link here to other Planning in London articles contributed by Gary Young.

Gary Young’s presentation to London Planning and Development Forum 3rd December 2109 illustrated summary:

The inspectors report on the London Plan states the requirement for meeting housing demand of 55,000 homes per year will not be met by homes planned on existing known sites. A green belt review is required but not planned until the earliest 2023. However the green belt and land adjacent the suburbs will not alone provide the answer to housing demand.

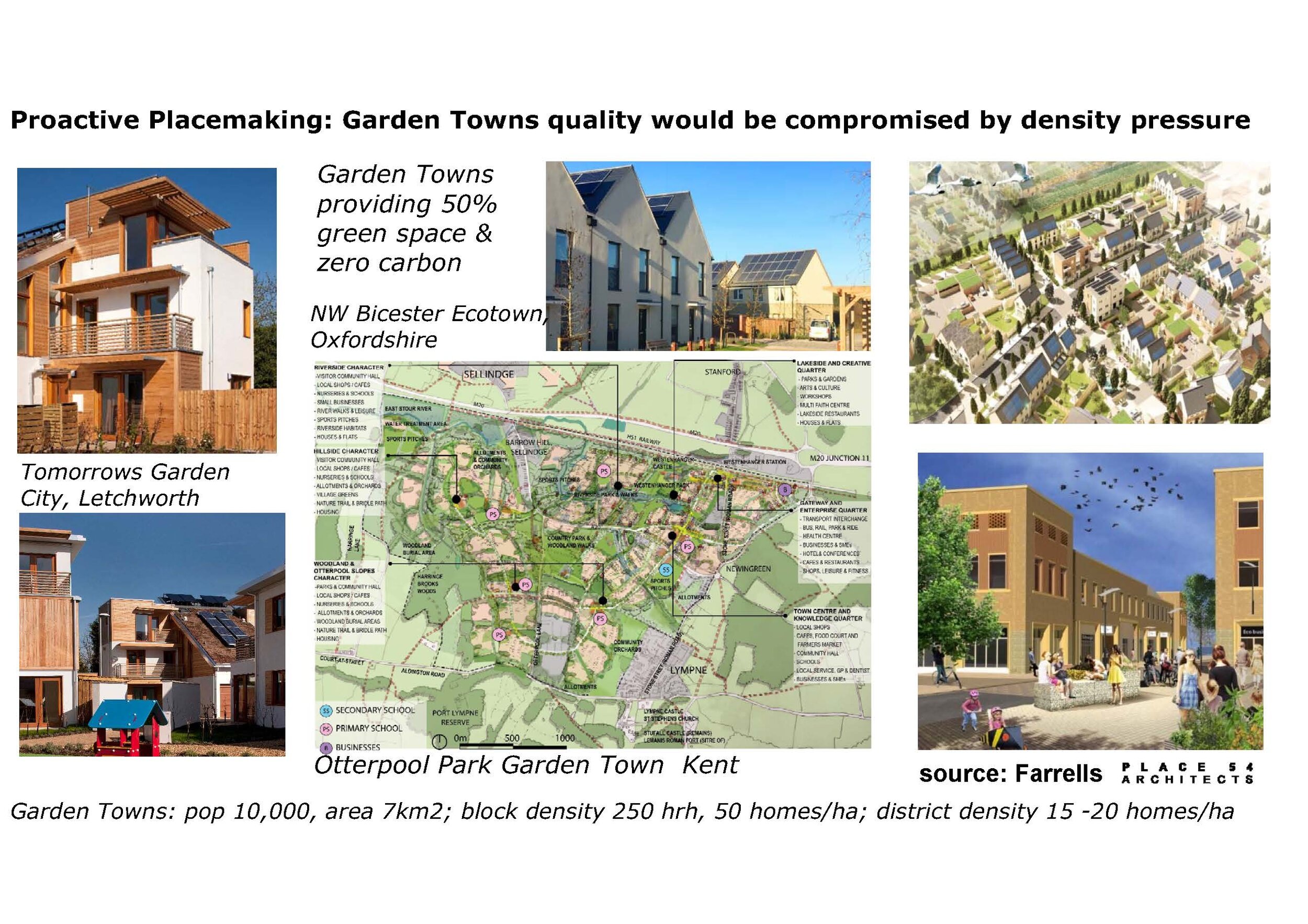

Designs based on garden city principles may create high quality places, however including the 50% green space garden towns achieve maximum district density of 20 homes per hectare. This would requires a significant amount of land for 55,000 homes per year, the equivalent to 5 garden towns. If planned for London’s Green Belt this would need 30-50 sq. kilometres per year and half of the available space in green belt could be consumed within 30 years. Planned Garden towns and urban extensions are typically in rural and suburban edge locations and typically have limited public transport accessibility. These locations in the early stages, are particularly vulnerable to undesired impacts on surroundings, e.g. increased traffic congestion, demand on services and economic viability dictating a lower density of housing to satisfy the market.

London’s Green belt will not provide an answer to the required housing with garden towns with densities typically of 50 per/ha. Garden town and suburb densities would consume a very large area of green belt to meet anticipated demand, which is neither possible nor an answer to the quality v overcrowding debate.

Therefore planners must seek appropriate alternative places to supply housing to meet demand. Opportunities areas in the south east including the Cambridge Arc could accommodate both employment and housing, require significant investment in new transport infrastructure, which at current trends is many years into the future.

Moreover the climate emergency requires urban areas to provide for the demand in housing at increased densities and green areas preserved and enhanced to provide environmental mitigation. Green areas are needed for increased tree planting to absorb Co2; creating habitats for biodiversity, for renewable energy production, providing cooling from the urban heat sink; to provide land for food production. It may not be possible for food or renewable energy self-sufficiency in the immediate location of a city, however food growing near urban populations is necessary to reconnect the awareness of how food is grown locally.

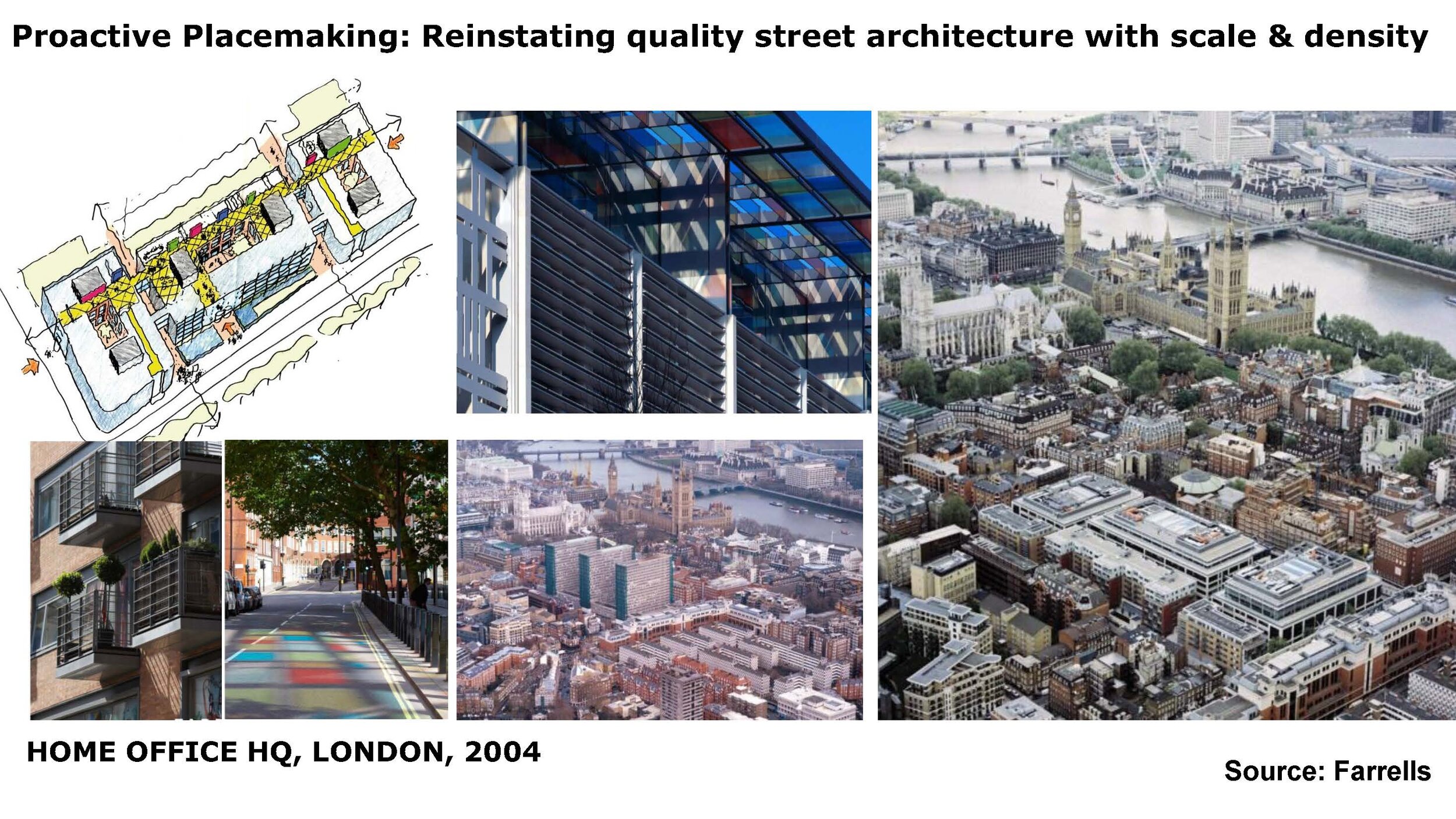

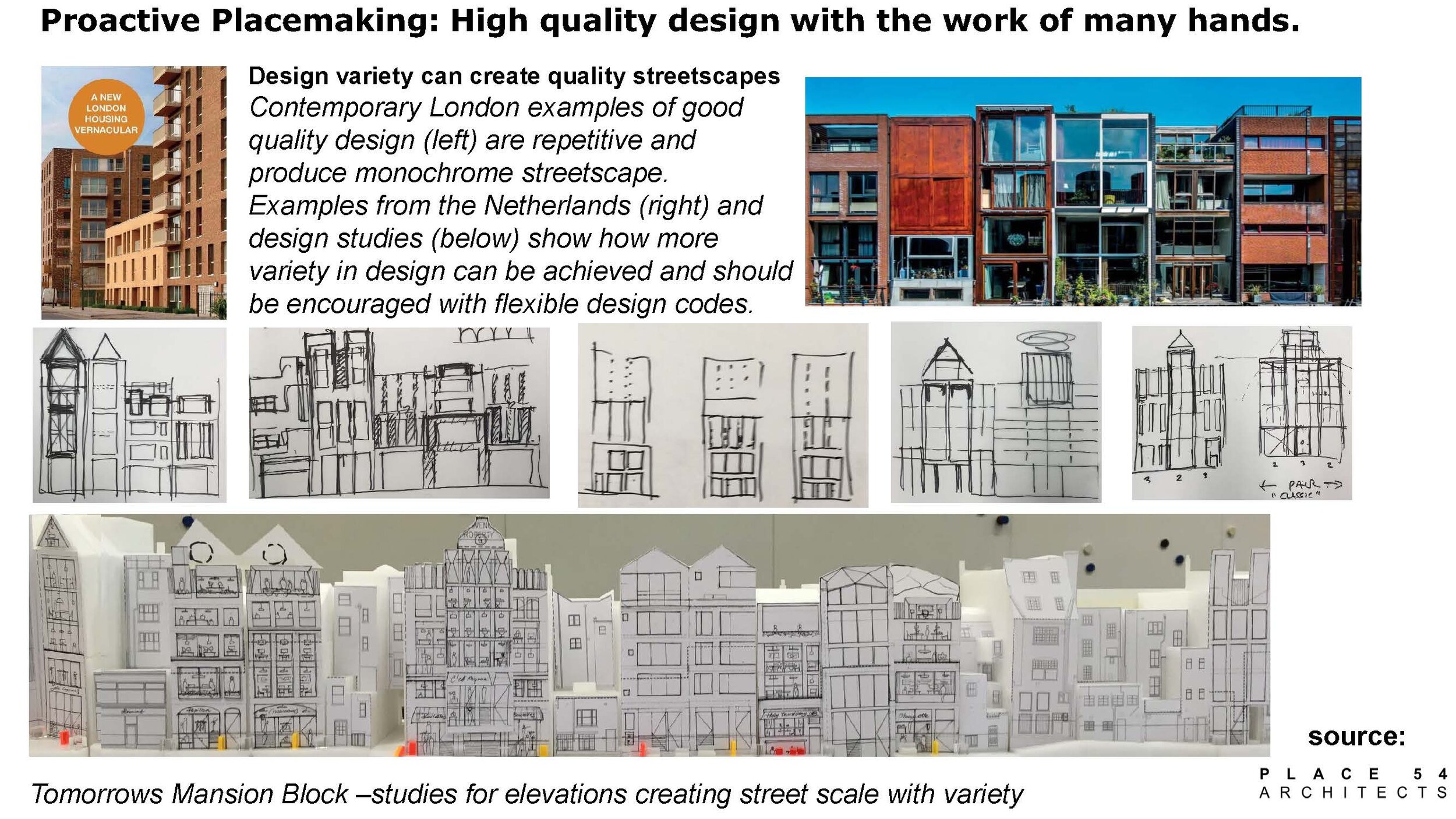

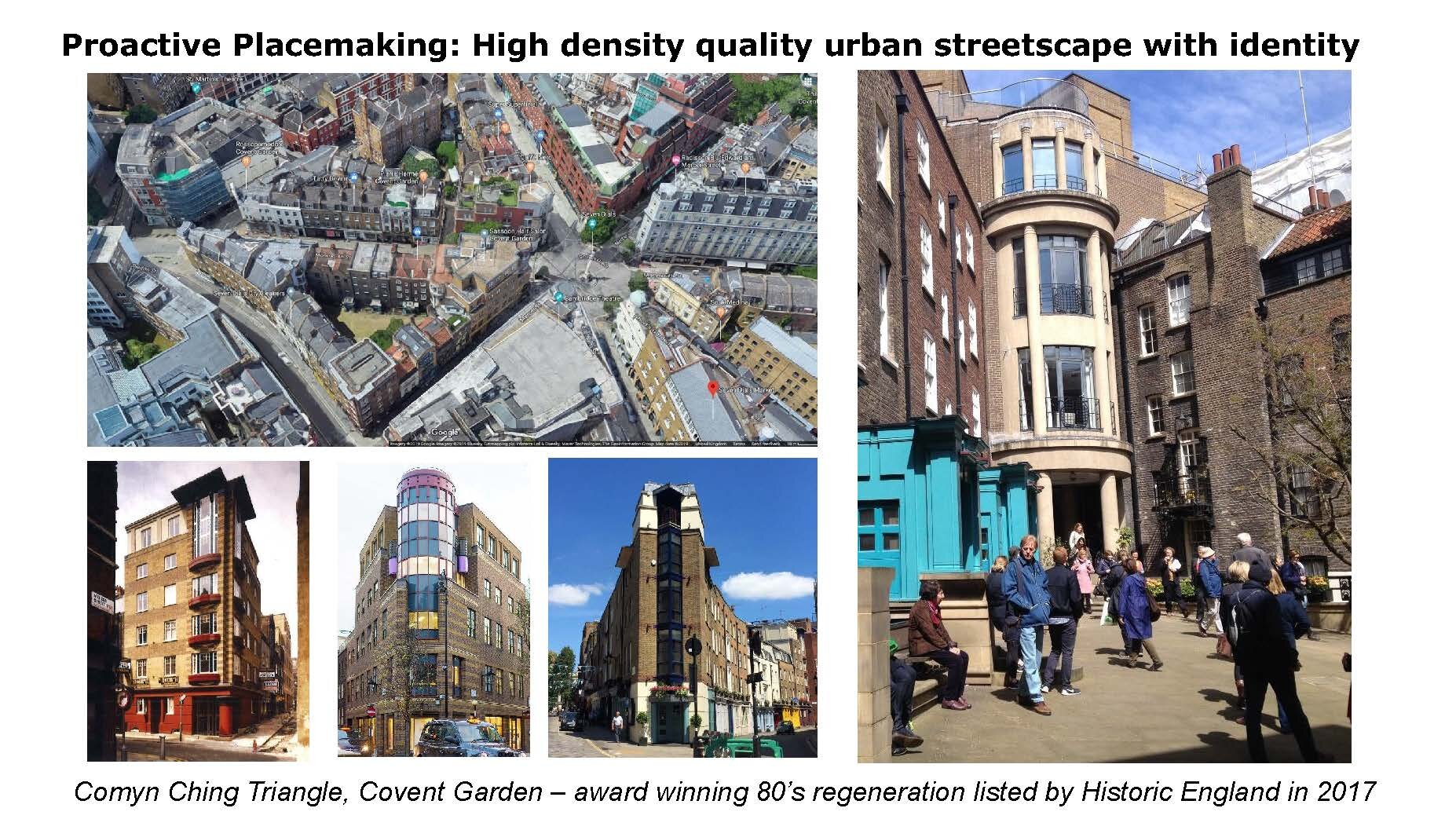

Recent planning permissions in inner London have been achieving high densities of 150 homes per ha which would increase housing provision offer a solution to the housing demand. However new designs are producing a proliferation of high rise residential towers and a reduced presence at street scale. Street scale architecture has historically created the distinctiveness of London. The decline of this distinctive character is a cause for concern where local individuality could be sacrificed for global branding, with housing mix less diverse, buildings and streets which lack human scale.

Increasing density for garden towns or suburbs up to 100 homes per ha and reducing green space, could be appropriate in a few locations, particularly where public transport infrastructure exists and investment can increase efficiency. Applied generally in greenbelt or suburbs these densities will however compromise garden city principles and existing housing character, will not be welcomed by existing residents.

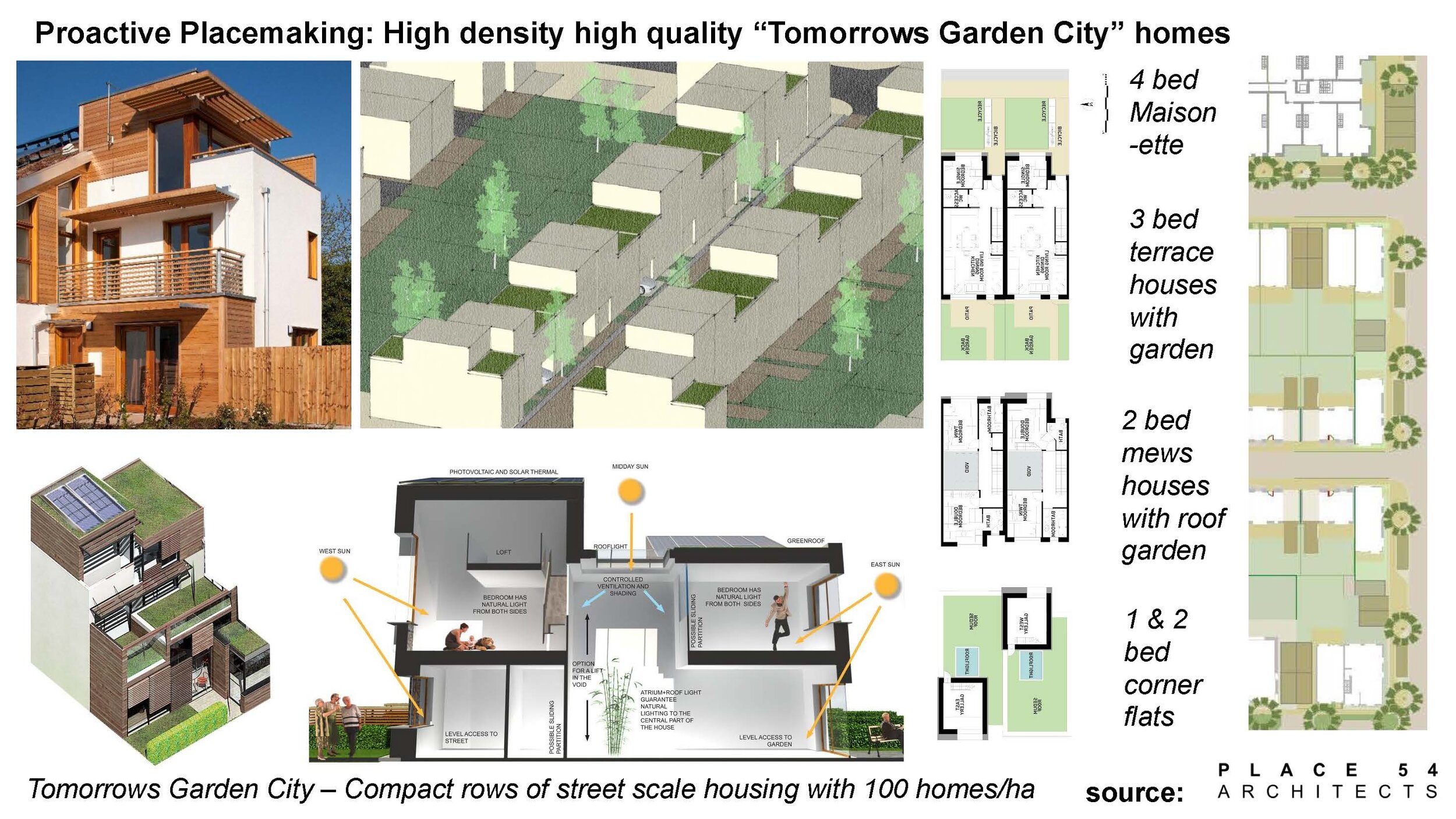

Good housing designs for terraces and street blocks can create densities of 100 to 150 homes per hectare. These designs require street enclosed blocks or terraces rather than detached blocks. The house typology will require narrower frontage widths, increased house depths and for larger homes will require 3 or 4 floors.

Case Study: 100 homes per/ha Tomorrows Garden City:

· Up to 100 homes per ha

· 3-4 storeys Street and Mews type Terraced houses

· Possible Staggered or scissor plan for maisonette flat mix

· Creating privacy with back to back roof amenity spaces

· Narrow plots with increased depth

· Wider plots reduced rear garden separation distance

· Reduced overall block depth, adaptability for corners

· Mix of wide front and narrow front house widths

· Character equivalent to London street and mews;

Issues:

· Irregular profiles can be more expensive to build,

· On plot parking reduced,

· Can be harder to sell in a comparative market.

· Careful design codes need to prevent erosion of design quality.

Achieving housing numbers requires increased density which has to be considered appropriately in different places. In London suburbs there are opportunities for infill housing at densities up to 100 homes per hectare with street terraces designs of up to 4 storeys.

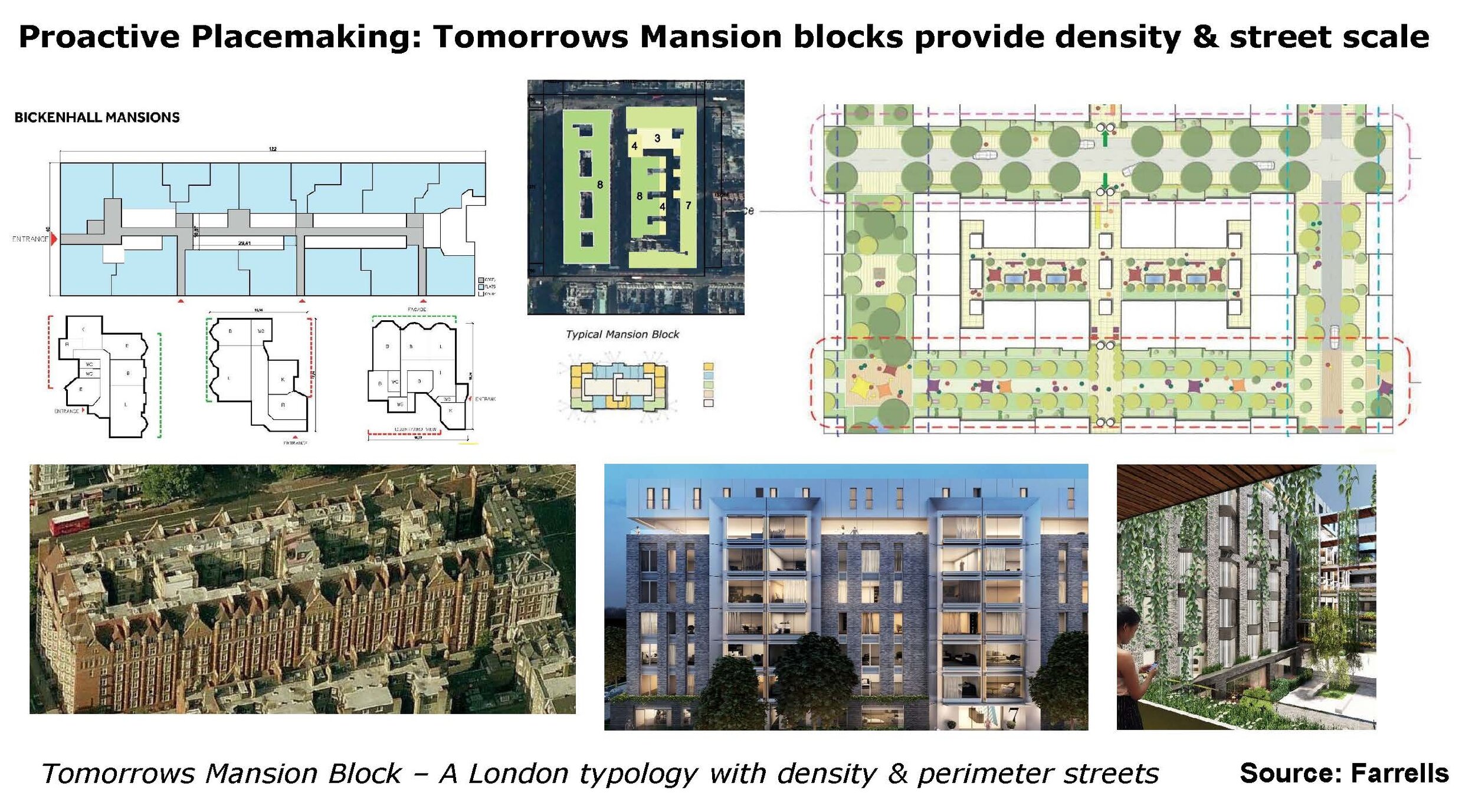

In inner London there are opportunities for new housing sites or integrating infill housing into existing areas, for example above railway tracks with higher densities of 150 homes to 200 homes per hectare whilst retaining a street block layout of maximum 8 floors using Tomorrows Mansion Block.

The most likely scenario for increasing housing supply is increased density in appropriate areas where transport infrastructure already exists and demand from existing housing and employment is already there. These conditions make infrastructure investment economically viable however will require new housing to be designed with qualities which are acceptable to existing articulate and organised residential neighbourhood groups. In this latter case the current trend towards residential towers is at risk of failing to achieve the necessary quality and integration into existing neighbourhoods if repeated over a large extent of London suburbs.

These areas where higher density could be achieved area at risk of losing character and quality of place from the trend towards creating clusters of high residential towers of 20 up to 40 storeys.

The case for Tomorrows Mansion Block

Tomorrows Mansion Block presents a solution for quality without overcrowding which can be achieved with design typologies such as mansion block and terraces. These typologies require the street and public realm to be restated as priorities and the primary infrastructure for higher densities.

Good placemaking practice and research supports street architecture heights of up to 6 – 8 storeys being the highest floor where residents can still relate well to activity in the street, hence creating neighbourhoods, which are key part of place making. Towers of 10 storeys upwards break this key relationship between residents and the activity in streets. neighbourhood created by active streets.

Neighbourhood are created by quality homes with active streets and good public realm. Good designs solutions which combine creative use of public realm on the lower floors of towers fronting streets can still achieve active streets and neighbourhoods, however the height of residential towers put the majority of residents beyond the view and hearing others in a street neighbourhood. This reduces the likelihood of natural surveillance of streets, reduces the amount of spontaneous interaction, thereby increasing isolation and wellbeing, ultimately reducing the likelihood of successful placemaking. Ref: Jane Jacobs: Life of American Cities.

Planning consents for new residential development in inner London are achieving 150 homes per /ha, however a large number of recent planning consents have resorted to towers to achieve these densities.

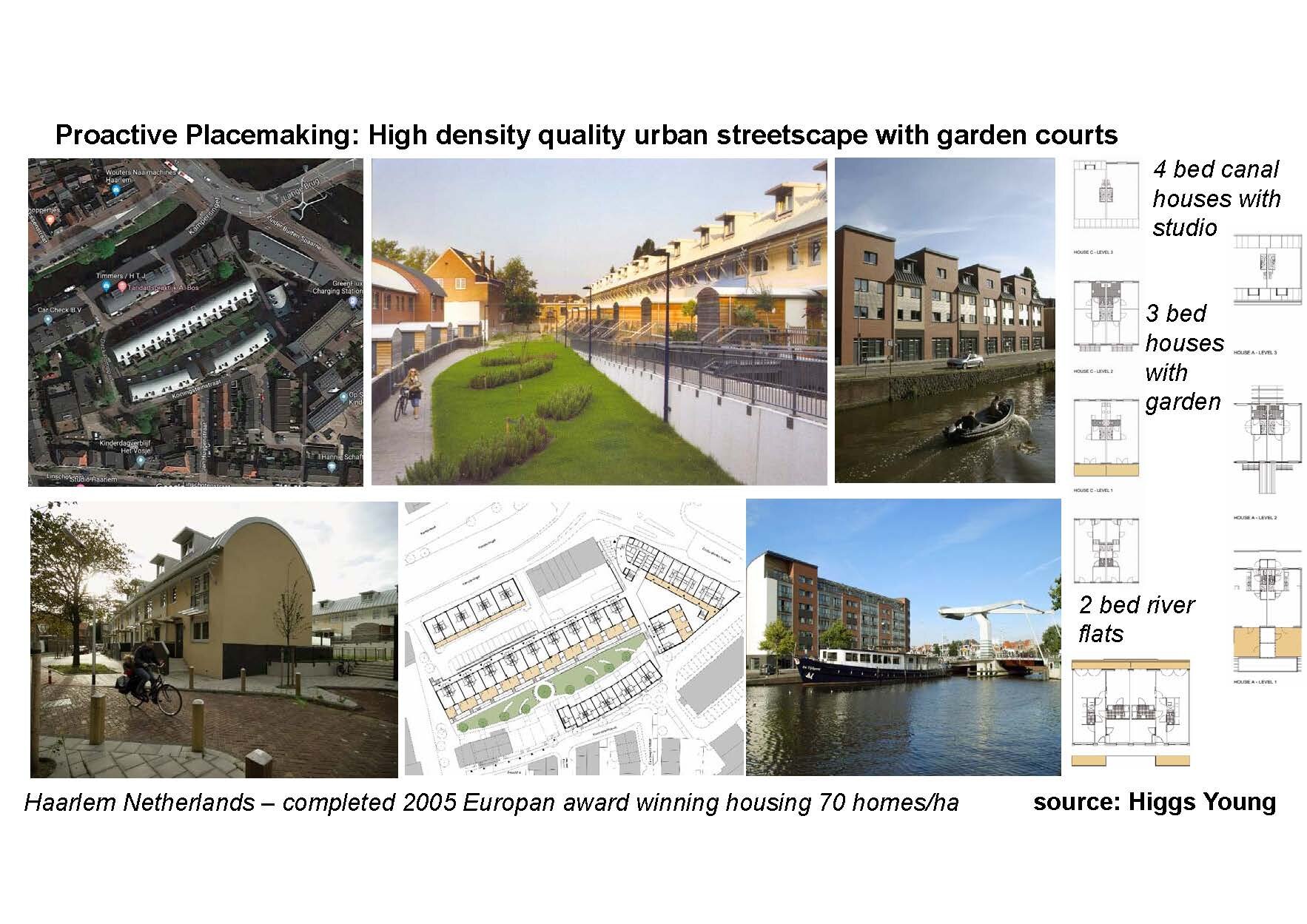

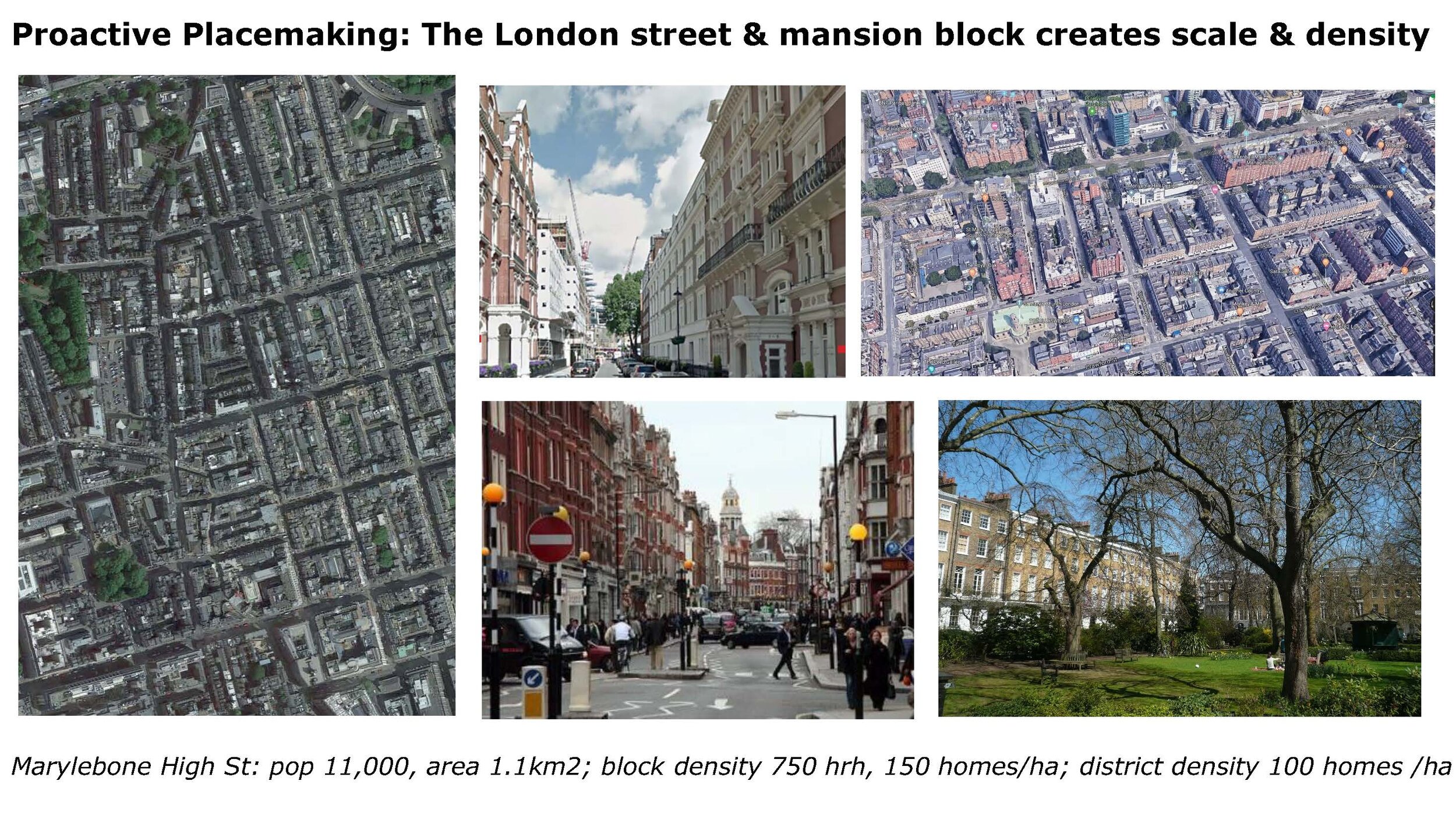

Precedents for Tomorrows Mansion Block – Paris and London

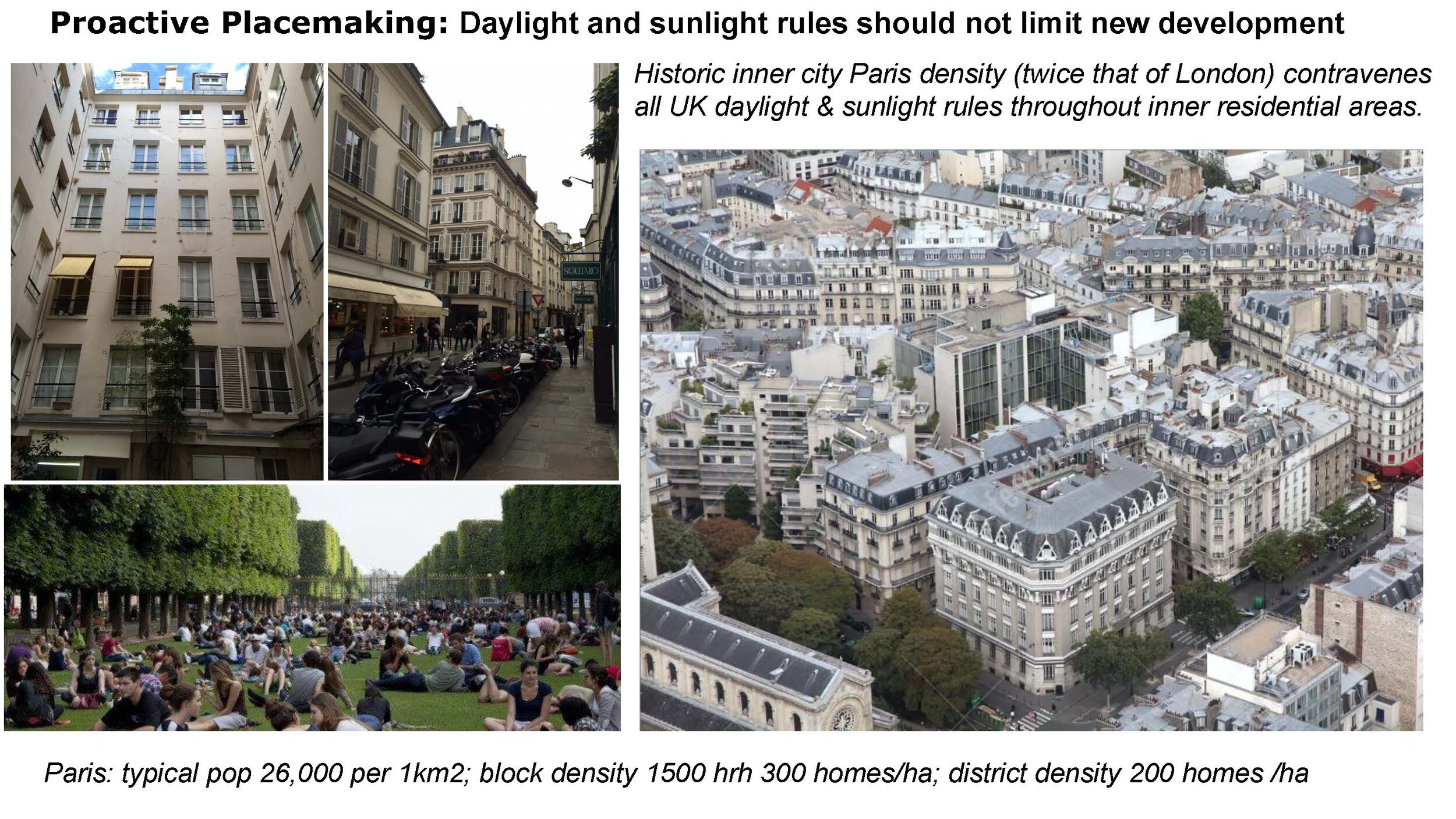

Existing urban design Examples taken from areas of Paris and Inner London demonstrate that density of between 200 homes per ha (Paris) and 150 homes per ha (Marylebone inner London) and are achievable with street scale architecture of 5 to 8 storeys. This raises the question why have residential towers been commonly introduced into the mix of housing in London.

There are several reasons for the trend towards residential towers. The private sale residential marketing emphasises views which has led to an increased demand for higher residential towers.

However there are alternatives to the tower, such as housing seen in Marylebone and Paris which is better street scale urban design would be promoted by planners and design guides for a higher quality place making solution.

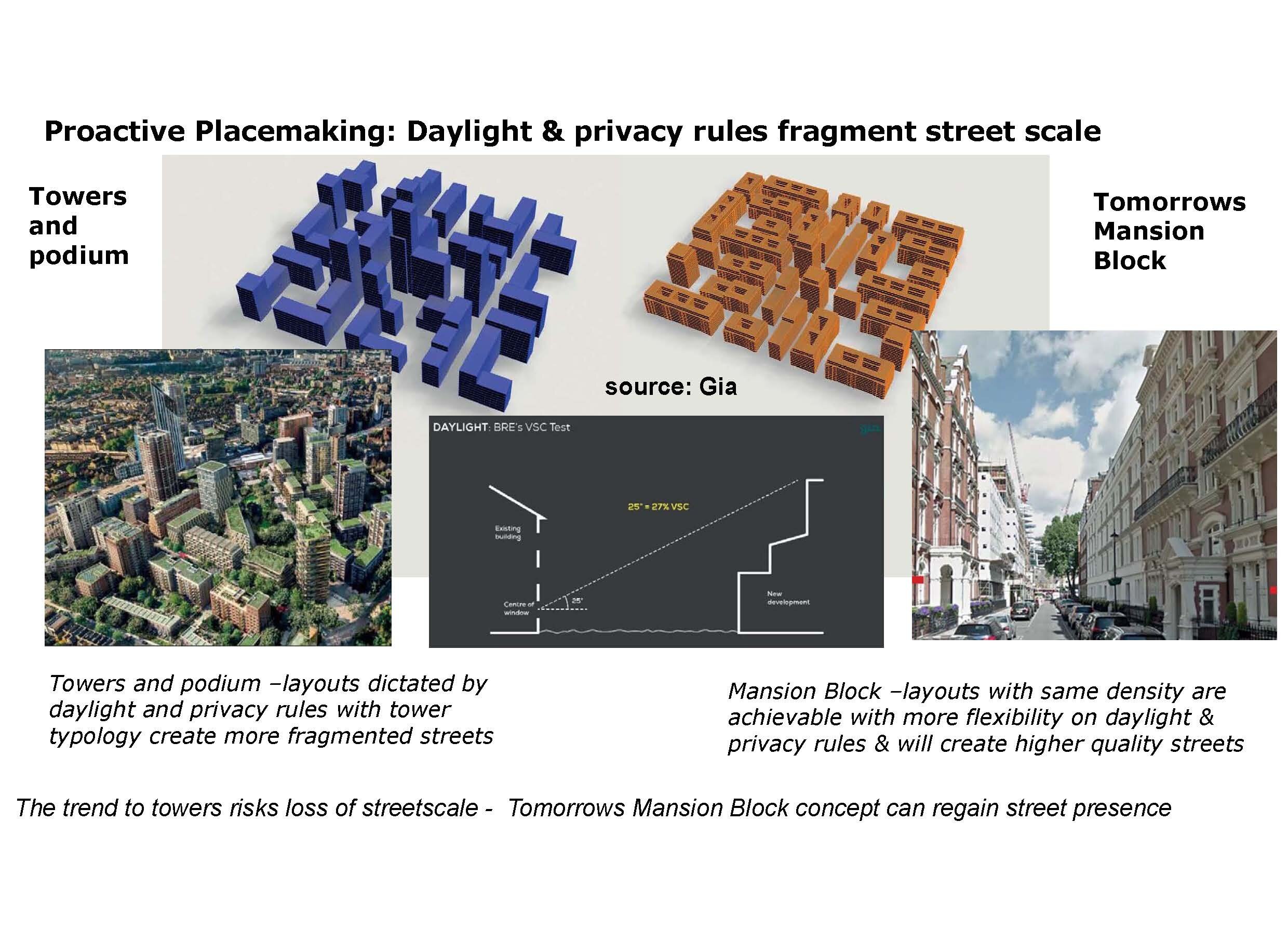

Street blocks and terraces at higher densities are not being designed as frequently as towers. The reason why fewer street blocks are designed is planning requirements which are specified to provide amenity which are inadvertently influencing spatial configuration and scale at higher density towards towers rather than street blocks. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century there was a need to create sanitary and hygienic living conditions, replacing a century of overcrowded dwelling conditions. This presumption for “light and air” described in many famously regarded architectural treatise, it then became a default requirement in residential regeneration and resulted in the twentieth century boom in building residential towers. The health needs have not changed, yet designs need a reconsideration in light if the complexities and changing priorities and requirements of balancing sustainable development, climate change caused overheating, improved thermal efficiency and building envelope, accessibility, placemaking, mental health and wellbeing.

Minimum privacy separation distance between habitable rooms is set at 18m as recommended yardsticks in London Housing Guidelines and mandatory in some London Borough plans. These privacy distances create restrictions which restricts layouts with inner courtyards in residential buildings. Whereas these lower rise blocks have in the past achieved high residential densities, with these current regulations the low rise courtyard block cannot comply and provide the same density as taller towers. In addition to privacy the daylight requirements for windows assume an angle of 25 to 30 degrees from horizontal as a guideline. This results in a restriction on height of closely spaced courtyard and street blocks at concept stage and a trend to disaggregated blocks to achieve the requirements. Disaggregated block become towers with higher density. Daylight studies can demonstrate that rooms will achieve adequate daylight in closely spaced courtyard blocks. Whilst it would be necessary to carry out the analysis early to keep in mind the options, the relaxation of prescriptive rules will encourage this innovation and return to a lower rise street block solution,

The same privacy distance and light angle requirements affect street frontage separation. In good urban design guidance streets are considered as a special case, where quality and character of street scale are paramount. This allows the design to create quality streets with increased height or narrower width, therefore in this instance privacy distances have been relaxed and reduced. This is essential when the character of London is made up of typical streets which can be 12m wide and mews which are 8m wide. However for inner courtyards or frontages which are not considered streets, or above ground on a podium, the required privacy and daylight separation distances make inner courtyards larger and home in inner corners harder to design. The typical response has therefore been disaggregation to isolate the block from a group, reduce the floor plan area and correspondingly to increase height into towers to achieve density.

In addition to minimum daylight angles a restriction on north facing single aspect flats makes a further challenge for street blocks with north aspect. This is a reasonable requirement to provide sunlight to living accommodation. To minimise north facing flats is another test for the ingenuity of Tomorrows mansion blocks which will demonstrate dual aspects for every flat, albeit within limits.

Combined together these three requirements restrict layout of residential blocks, encouraging towers at higher densities and precluding the mansion block and street typology. This has resulted in an increase in high rise residential and a loss of engagement with the street.

Recently designers have channelled effort using expertise in daylight studies to pressure for this greater flexibility and need to continue persuading plan makers that more that flexibility in regulations will allow the return of the mansion block and other high density lower rise housing in street and terrace forms. These typologies will regain the connection with residents and the street and reinforce the character and place. expertise in daylight studies is need to pressure for this greater flexibility.